SDL on Linux

In my forthcoming ebook, which is the Linux equivalent of the first one I use Visual Studio Code (VSC) as the IDE to develop along with the Microsoft C/C++ extension. I’m using the SDL2 library for fast graphics and Clang as the compiler.

Thankfully Microsoft have documented most of the process of using Clang with VSC, albeit on a Mac. I’m using Ubuntu but it’s mostly the same.

Before I could configure SDL I had to add it and I never realised about apt-cache on Ubuntu (and Debian). The command

apt- cache search libsdl2

Outputs this, showing what's available.

libsdl2-2.0-0 - Simple DirectMedia Layer libsdl2-dev - Simple DirectMedia Layer development files libsdl2-doc - Reference manual for libsdl2 libsdl2-gfx-1.0-0 - drawing and graphical effects extension for SDL2 libsdl2-gfx-dev - development files for SDL2_gfx libsdl2-gfx-doc - documentation files for SDL2_gfx libsdl2-image-2.0-0 - Image loading library for Simple DirectMedia Layer 2, libraries libsdl2-image-dev - Image loading library for Simple DirectMedia Layer 2, development files libsdl2-mixer-2.0-0 - Mixer library for Simple DirectMedia Layer 2, libraries libsdl2-mixer-dev - Mixer library for Simple DirectMedia Layer 2, development files libsdl2-net-2.0-0 - Network library for Simple DirectMedia Layer 2, libraries libsdl2-net-dev - Network library for Simple DirectMedia Layer 2, development files libsdl2-ttf-2.0-0 - TrueType Font library for Simple DirectMedia Layer 2, libraries libsdl2-ttf-dev - TrueType Font library for Simple DirectMedia Layer 2, development files

So a quick

sudo apt-get install libsdl2-dev

Installed 73 MB of files including all the header files. I used the files app to search for SDL files and it found a folder SDL2 in /usr/include.

And all I needed in my program was

[perl]

#include <SDL2/SDL.h>

[/perl]

And I had to add “/usr/include/SDL2/” into the includePath section of c_cpp_properties.json and “-lSDL2” into the args section of tasks.json. These two JSON files are included in C/C++ projects in VSC.

At that point I could compile and run my first SDL program on Ubuntu. It throws 10,000 random sized coloured rectangles onto the screen

This bit is slightly controversial. I find all the * makes it harder to read code so I use typedefs to hide them. Here’s an example from the game. Try replacing every pbte with byte * and see if reading it is harder for you.

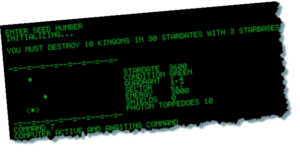

This bit is slightly controversial. I find all the * makes it harder to read code so I use typedefs to hide them. Here’s an example from the game. Try replacing every pbte with byte * and see if reading it is harder for you. That thing in the top right corner of the page that says GAME SOURCES? That’s a list of pages on the site and it’s the first and currently only page apart from the main blog. I’ve added a game conversion that I wrote back in 2006 when I was learning C (I mean comments are /* n.. */ none of this modern // stuff!).

That thing in the top right corner of the page that says GAME SOURCES? That’s a list of pages on the site and it’s the first and currently only page apart from the main blog. I’ve added a game conversion that I wrote back in 2006 when I was learning C (I mean comments are /* n.. */ none of this modern // stuff!). There are four types of moving object in the games. Asteroids in four sizes from 35×35, 70×70, 140×140 and 280×280 pixels, the player’s ship (fits in 64 x 64 pixels), alien ships (also in 64 x 64) and a bullet which is solid 3×3 pixels with the four corners empty.

There are four types of moving object in the games. Asteroids in four sizes from 35×35, 70×70, 140×140 and 280×280 pixels, the player’s ship (fits in 64 x 64 pixels), alien ships (also in 64 x 64) and a bullet which is solid 3×3 pixels with the four corners empty. This is an invisible square that just fits round each object. For the player’s ship it’s 64 x 64 and it corresponds to the sizes of each asteroid. As the image shows, the two bounding boxes overlap and it’s in this overlap rectangle that we have to check for a possible collision.

This is an invisible square that just fits round each object. For the player’s ship it’s 64 x 64 and it corresponds to the sizes of each asteroid. As the image shows, the two bounding boxes overlap and it’s in this overlap rectangle that we have to check for a possible collision. First things first. Every frame all objects are moved and we have to detect if there’s a chance of a collision. This is done by dividing the entire playing area (set in the book to 1024 x 768) into 64 x 64 pixels cells. I chose that as a convenient size. Once the object’s new x,y location has been calculated, I determine which cells it overlaps.

First things first. Every frame all objects are moved and we have to detect if there’s a chance of a collision. This is done by dividing the entire playing area (set in the book to 1024 x 768) into 64 x 64 pixels cells. I chose that as a convenient size. Once the object’s new x,y location has been calculated, I determine which cells it overlaps. The next bit is what makes it pixel perfect. For every object and its rotations, I have created a mask. It’s a file of bytes with a 1 value corresponding to every coloured pixel in the object and 0 to empty pixels.

The next bit is what makes it pixel perfect. For every object and its rotations, I have created a mask. It’s a file of bytes with a 1 value corresponding to every coloured pixel in the object and 0 to empty pixels.

Today I found out about

Today I found out about